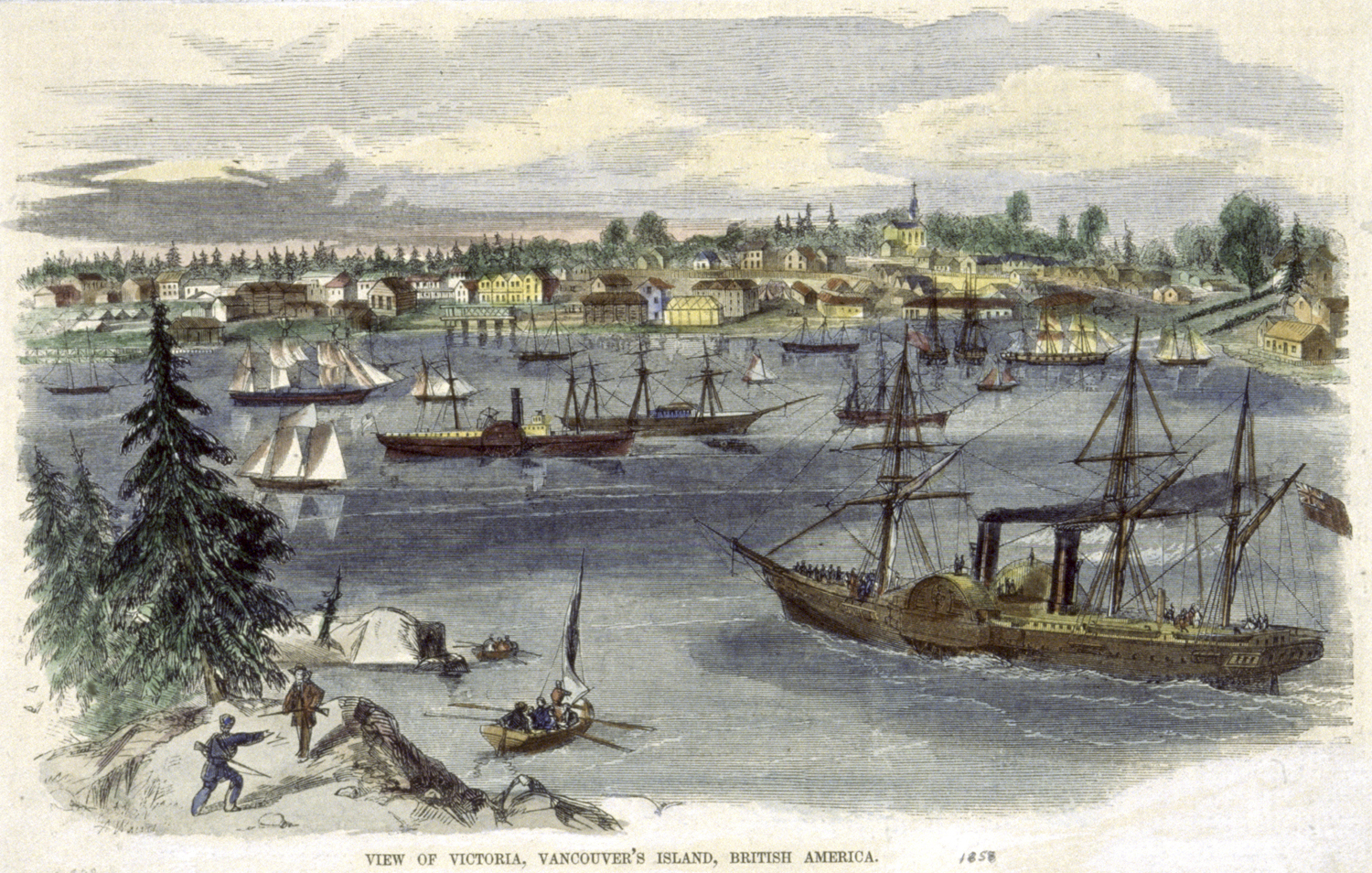

Circa 1858 or 1859 Correspondent’s rendering, Image PDP01898: courtesy of the Royal BC Museum

Probably the best reward for my having been so well immersed in researching our West Coast maritime history over the years, was coming across certain aspects of it that have never been written up let alone spoken to in the past. What with having been born and raised in Victoria, a city whose history and culture was supposedly all of British origin, I was much surprised to discover how so closely linked it was with ports down along the U.S. west coast throughout the later half of the 19th century. Indeed the tentative title of my current book project is Twin Cities: Victoria and San Francisco.

Regardless of its longstanding British standards and social habits, Victoria in its early formative years was transformed into very much an American wild-west frontier town after becoming so closely linked to San Francisco both socially and economically back in the mid-1800s. To start with, both cities are somewhat similar geographically what with their being bounded by ocean waters on three sides. As it is, San Francisco remains as one of the largest ports along the Pacific since this unique geographic feature protects an incredibly large open bay. Although its harbor is much smaller in size, Victoria was to become another very active port along the Pacific coast of the Americas. Fort Victoria, a quiet and peaceful Hudson Bay Company trading post, underwent a dramatic transformation once the Fraser River gold rush of 1858 was underway and both Vancouver Island and New Caledonia (today’s mainland British Columbia) were absolutely overrun with Yanks eager to pan a good dollar out of the river bars. Victoria, which was to be transformed into just another American wild west town, was to maintain its close ties with California right up until the arrival of Canada’s trans-continental railway, the C.P.R. (Canadian Pacific Railway) to Pacific tidewater at Port Moody in the summer of 1886.

But regardless, as time went on I finally began to unravel and get to the bottom of the story as to how British Columbia’s capital city was so closely connected to the U.S. west coast throughout the 19th century. Having been totally immersed in researching and writing west coast maritime history over the years, one particular shipwreck I became obsessed with, and whose remains are still yet to be found, was that of the U.S. flagged steamer George S. Wright which was lost on a voyage returning to Portland, Oregon, after a run freighting mail and cargo up to Alaska. It was while scanning through Victoria’s paper of the day, the British Colonist, tracking news of her disappearance and loss, that it really came across how much sea-going traffic remained running between U.S. ports and Victoria well into the later years of the nineteenth century. On February 28th, 1873, residents of Victoria opened their copies of the Daily British Colonist to read, “Terrible Marine Disaster!” Probable Loss of the Propeller Geo S Wright with all on board!” The American screw steamship was on its way south from Alaska to Portland in late January that year.

The Captain of the George S. Wright took on some risk and put all her crew and passengers in danger by taking the outside route through Hecate Straits to cross Queen Charlotte Sound rather than through the Inside Passage that winter. As it was, the steamer which was only 117 feet in length and of 184 gross tons, would have been overloaded with all the cargo and passengers they had taken on. Captain Thomas J. Ainsley had put to sea from Kluvok, their final Alaska stop, after loading some 800 barrels of salmon, 100 barrels of oil, along with some skins and furs on 25th January. They then headed out into a snow storm which would have made for treacherous sea conditions out in Hecate Straits. Still her Captain was most keen to get back into Victoria as soon as possible since he was engaged to a woman who lived there. The steamer was under the command of Captain Ainsley, “an experienced pilot” who, as it happened, was “…the brother of a Mrs. Mouat of this city” according to the British Colonist. In its March 7th paper, it went onto provide a list of the steamer’s officers and crew and reported that “Capt. Ainsley, it is stated, was shortly to have been married to a young lady of this city…Chief Engineer (John) Sutton leaves a large family in this city; so, too, does Assistant Engineer Minor; B.F. Weidler, the Purser, was a brother of George W. Weidler, steamship agent here.”

Victoria’s harbour was to remain an incredibly busy port following the Fraser River gold rush what with steamers and ships of sail arriving in from Portland and San Francisco as well as ports throughout Puget Sound. The local papers would keep track of ships tied up in Victoria’s Inner Harbour or over in Esquimalt waiting their turn to unload and listed not only all the goods being delivered up onto her wharves but also all the passengers aboard and what they were here for This flurry of activity continued on well into 1859 and in its June 25th paper that year Victoria’s British Colonist reported on how the city had come to the forefront as a major marine centre on the Pacific by listing the ships currently sitting in port at both Victoria and Esquimalt at the time: the steamers Otter, Governor Douglas, Caledonia, Colonel Moody and Eliza Anderson; the ships Thames City, Carnatic, Eliza and Ella, barks Euphrates, Carrie Leland and Caesar, brigs Katie Foster and Hamburg, steamship Forward, along with the Royal Navy’s Tribune, Satellite, Pleiades and Plumper.

In essence, the boundary between the United States of America and what was British territory at the time never really stood for much throughout the years following the Fraser River gold rush right up until July 1871 when the colony finally joined Confederation as the province of British Columbia.